Displacement and Distance with Examples

In this article, examples of displacement and distance in physics are presented along with their definitions which is helpful for high school physics.

Definition of displacement and distance

Displacement is a vector quantity describes a change in position of an object or how far an object is displaced from its initial position and is given by below formula \[ \Delta \vec x = x_f - x_i \] where the starting and ending positions are denoted by $x_i$ and $x_f$, respectively.

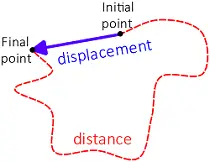

Distance is a scalar quantity indicating the total path traveled by a moving object.

Since in both cases, the interval between two points is measured- one as the shortest line and the other as the total traveled path- the SI unit of displacement and distance is the meter.

The illustration below shows the difference between them clearly.

Examples of displacement and distance

Now with this brief definition, we can go further and explain those concepts more concisely with numerous examples.

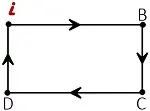

Example (1): A boy is playing around a rectangular path. He starts his game from one corner ($i$) and ends at the same one. Specify its displacement and distance traveled.

Solution: Since the boy's initial and final positions are the same, by definition, his displacement is zero.

On the other hand, the total distance traveled by him is the perimeter of that rectangular shape.

Example: A car travels a circle of the circumference of $100\,\rm m$. In each of the following, find the quantity wanted:

(a) If the car moves once around the track, what is the distance traveled by it? What if it moves twice?

(b) If the car moves once around the track, what is its displacement?

Solution: Here is another example of displacement to clarify its difference from the distance traveled.

Distance is defined as the total path covered by a moving object, whereas displacement refers to the difference between the initial and final positions of the moving body.

(a) The total path taken by the car around the circle corresponds to its circumference. When the car travels one full revolution around the circle, its distance traveled is $100\,\rm m$.

If the car completes two full revolutions, the total distance traveled becomes $200\,\rm m$.

(b) For displacement, when the car completes a full revolution around the circle, its initial and final positions coincide. According to the definition of displacement: $\Delta x=x_f-x_i$. In this case, since $x_f=x_i$, the displacement is zero ($0$).

This example clearly illustrates that the distance traveled can never be zero, even though the displacement may be zero in certain cases.

Note: The symbol $\Delta$ (Greek letter delta) stands for "change in". In short, $\Delta x$ means "the change in $x$" or "the change in position", which is defined as displacement.

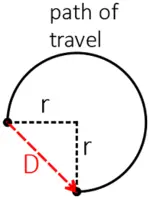

Example (2): A biker rides into a horizontal loop of a radius of 10 meters and covers three-fourths of it as follows. What are the displacement and distance traveled by him?

Solution: As mentioned earlier, displacement is a quantity that depends only on the position of initial and final points.

Thus, the straightest line between those points, which gives the magnitude of the displacement vector, is computed by Pythagorean theorem as

Thus, the straightest line between those points, which gives the magnitude of the displacement vector, is computed by Pythagorean theorem as

\begin{align*} D^2 &= r^2 + r^2 \\ &= 2 r^2 \\ \Rightarrow D &= r\sqrt{2} \end{align*} where the magnitude of displacement denoted by $D$. Putting the values gives, $D=10\sqrt{2}\,\rm m$.

Distance is simply the circumference of three-fourths of the circle, so \begin{align*} \text{distance}&= \frac{3}{4} \, {\text{perimeter}} \\\\ &=\frac{3}{4} (2\pi\,r) \\\\ &= \frac{3 \times 2\times \pi \times 10}{4} \\\\ &=15\,\pi \,\rm m \end{align*}

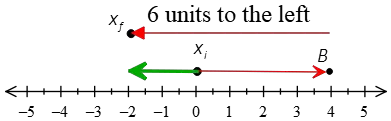

Example (3): A person starts at position 0 and walks 4 meters to the right, returns, and walks 6 meters to the left.

(a) What is displacement?

(b) What is the distance traveled by him?

Solution: Denote the initial position as $x_i=0$ and the final position as $x_f$. As you can see, from the starting position to the turning point, the person walks 4 meters to the right. From that point ($B$) count 6 steps to the left to reach the final point whose position is on the negative side of the axis, i.e., $x_f=-2$.

(a) Displacement in physics is a vector and is defined to be the final position minus the initial position. So, \[\Delta x=x_f-x_i=-2-0=-2\,{\rm m}\] Hence, the person displaced 2 meters to the left (green arrow). Here, the minus sign indicates the direction of the displacement (to the left).

(b) For the first part of the trip, the person walks 4 meters, and next, 6 meters more to the left. Thus, the total distance traveled is calculated to be 10 meters.

For one-dimensional motion along the $x$ axis, a vector pointing to the right is positive, whereas a vector pointing to the left comes with a negative sign.

Example (4): If you walk exactly 4 times around a quarter-meter path, what is your displacement?

Solution: Starting at an initial position $x_i=0$, you complete 4 full laps around the path. Since you end up back at your starting point, the initial and final positions are the same. Therefore, your displacement is zero.

Example (5): A bee starts at its hive and flies 500 meters to the east. Then, it flies 400 meters back to the west. Finally, it flies 700 meters to the east again. How far is the bee from its hive now?

Answer: "How far ... from the starting point" means finding the displacement. Displacement involves considering direction. Let’s take the east direction as positive.

First Flight: The bee flies $500$ meters east, so we write this as ($d_1 = +500\,\rm m$).

Second Flight: The bee flies $400$ meters west, so we write this as ($d_2 = -400\,\rm m$).

Third Flight: The bee flies $700$ meters east, so we write this as ($d_3 = +700\,\rm m$).

The total displacement is the algebraic sum of all partial displacements: \begin{align*} d_{tot} &= d_1 + d_2 + d_3 \\ &=(+500)+(-400)+(+700) \\ &= +800\,\rm m\end{align*} Therefore, the bee is $800$ meters east of the starting point since we obtained a positive sign for displacement.

If instead, we simply sum all the segments of the bee's journey, without considering the direction, the total distance traveled is obtained. Therefore, \[\text{distance}=500+400+700=1600\,\rm m\]

Example (6): A car moves around a circle of radius of $20\,{\rm m}$ and returns to its starting point. What is the distance and displacement of the car? ($\pi = 3$)

Solution: As mentioned above, displacement depends on the initial and final points of the motion. Because the car returns to its initial position, no displacement is made by the car.

The amount of distance traveled is simply the perimeter of the circle (since this scalar quantity depends on the form of the path). So $d=2 \pi r=2 \times 3 \times 20 =120\,{\rm m}$, where $r$ is radius of the circle.

Example (7): You walk once around an oval track for 6.0 minutes at an average speed of 1.7 m/s.

(a) What is the distance traveled?

(b) What is the displacement?

Solution:(a) Here, the distance covered by the person is the perimeter of the ellipse. Since the time elapsed and average speed are given, we can use the definition of average speed and solve for the distance traveled to find it as below \begin{align*} \text{average speed}&=\frac{\text{distance}}{\text{time interval}}\\1.7&=\frac{d}{6\times 60\,{\rm s}}\\ &\\ \Rightarrow d&=\big(1.7\,{\rm \frac ms}\big)(360\,{\rm s})\\&=612\quad {\rm m} \end{align*}

(b) Displacement is the difference between initial and final positions. In this problem, since the person has returned to his original position, his displacement is zero.

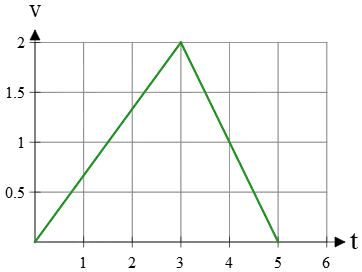

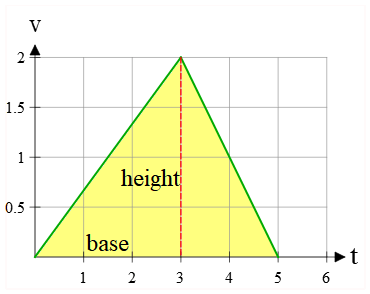

Example (8): The velocity versus time graph of a car is shown below. Find the displacement in 4 seconds.

Solution: The area under a velocity-time graph in a given time interval indicates the displacement in that interval.

In this case, the bounded area represents a triangle with a base of 5 units and a height of 2 units. The area of the triangle, which corresponds to the displacement, is calculated as follows: \begin{align*} \text{area=displacement}&=\frac 12 \times base\times height\\\\&=\frac 12 \times 5\times 2\\\\&=5\quad {\rm m}\end{align*} Thus, this car displaces 5 meters in 5 s.

Conclusion

Displacement is a vector quantity that depends solely on the initial and final positions of an object, without regard to the details of the motion or the path taken. Being a vector, displacement requires both a magnitude (length) and a direction to be fully described. It can also be determined from a position vs. time graph.

In contrast, distance is a scalar quantity characterized only by its magnitude. Unlike displacement, distance is path-dependent, as it reflects the total length of the path traveled by the object.

In general, the total distance traveled is not the same as the magnitude of the displacement vector between two points. If a moving object changes direction during its journey, the total distance traveled exceeds the magnitude of the displacement.

Both quantities share the same SI unit—meters—and are frequently used in problems involving velocity and acceleration.

Author: Ali Nemati

Date Published: 26 July, 2017

Last Update: Sep 7, 2024

© 2015 All rights reserved. by Physexams.com

AP® is a trademark registered by the College Board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse, this website.